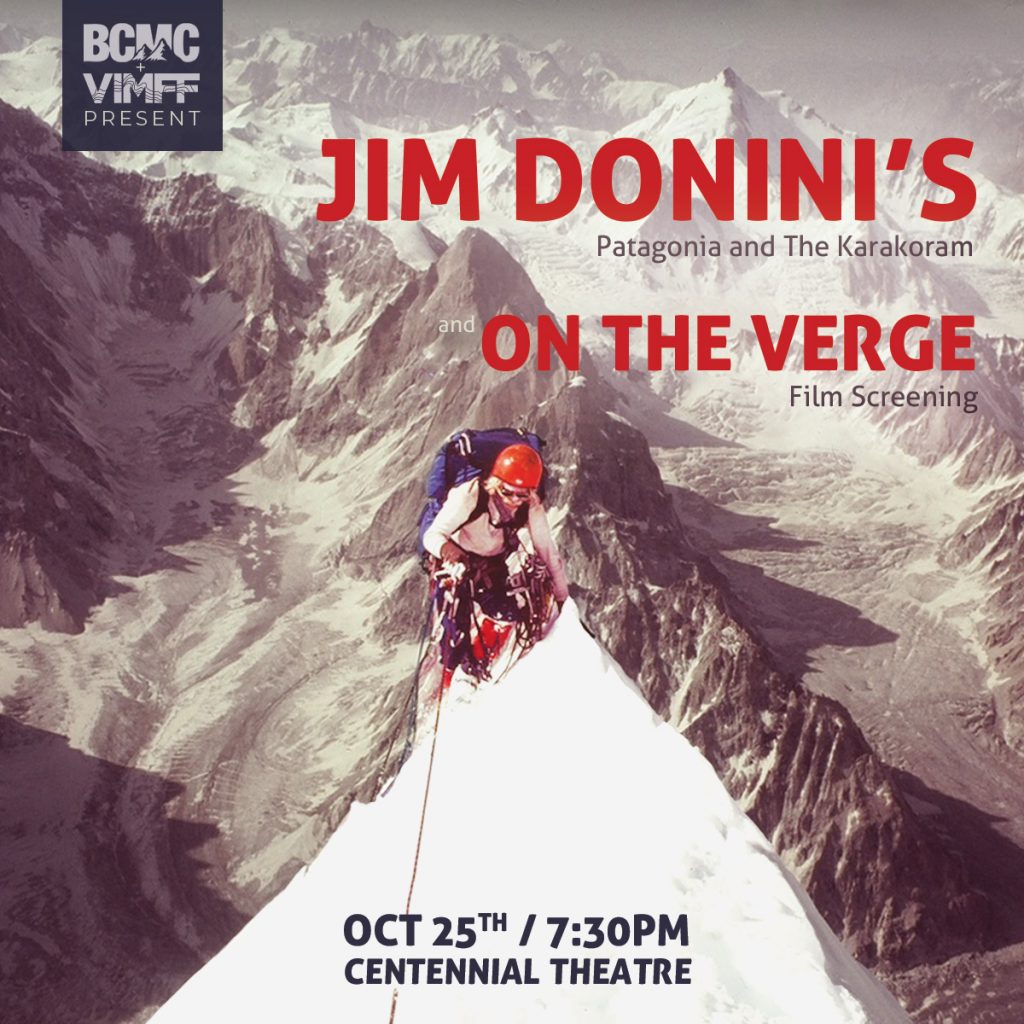

American Alpine legend Jim Donini will be sharing his stories of the Karakoram and Patagonia on Friday Oct 25, 2019, Centennial Theatre in North Vancouver.

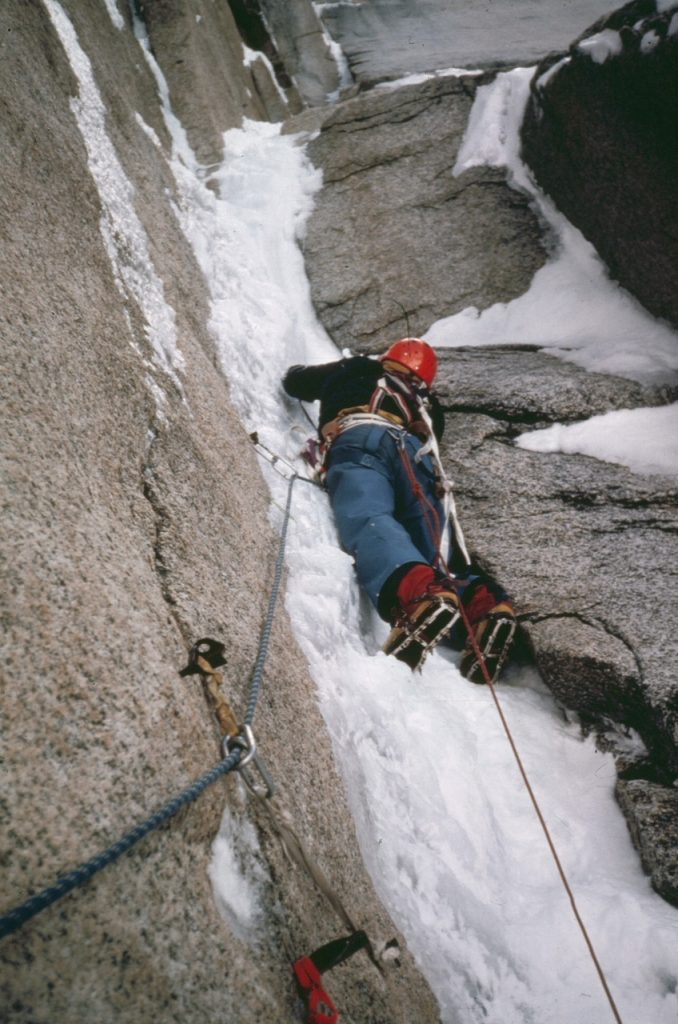

Jim Donini on a stormy summit day of Torre Egger

Jim Donini was first introduced to climbing while serving in US Army Special Forces in the mid sixties, launching an alpine climbing career that would last four decades. Known for making the first ascent of first ascent of Torre Egger in Patagonia, Jim has been a part of more than 40 alpine expeditions throughout the world. Jim served as President of the American Alpine Club from 2006 until 2009 and is the recipient of the Underhill Award for outstanding mountaineering achievement, the Angelo Heilprin Citation for exemplary service and Honorary Membership…the American Alpine Club’s highest award. Recently, he ascending Cerro Chueco in the Aysen region of Patagonia in and has made three expeditions to the Karakoram in the last four years, celebrating his 76th birthday on the Biafo glacier only a few weeks ago.

We had a chance to sit down with Jim and ask him a few questions in anticipation of the show this week. Here is what he had to say.

First off, thanks for taking the time to chat with us. Later this month, you will be taking the ViMFF stage to share your experiences in the Karakoram and Patagonia. What can our readers expect from a night full of stories and what are some of the things you will be sharing?

In 2016 I found myself along with George Lowe and Thomas Huber in the Latok / Ogre Cirque, in my mind, the most awe inspiring and beautiful mountain cathedral on the planet. George and I were returning to the scene of our epic 26 day climb on Latok’s North Ridge in 1978 and Thomas was there trying to put the finishing touches on what we had started.

The three of us talked about the various mountains where we had plied our craft and agreed that another mountain cirque 17,000 kilometres to the southwest rivalled the Latok/Ogre cirque in both beauty and difficulty. This is the Fitzroy/Torre Cirque in Patagonia.

I have had the privilege to have done pioneering climbing in both areas…the first ascent of Torre Egger in 1976 and our near miss on Latok’s North Ridge in 1978. I have also had five decades of experience with other notable climbs in both places, having just returned from my most recent trip to the Karakoram two months ago. I consider these two widely separated massifs to be crucibles of granite alpine climbing in the world.

The intent of my show is to introduce the audience to these two very special and stunningly beautiful places. Additionally, I want to show the changes that have occurred in these areas over the past forty plus years.

The three Torres in Patagonia. Photo by Jim Donini

Things certainly must have change in these regions throughout the years. Can you tell us bit about then and now?

In 1976 getting to the Fitzroy / Torre Cirque took some doing. The roads through the Patagonia desert were unimproved dirt and major rivers were crossed in tiny two car ferries. Now the previously small gaucho town of El Calafate has five star hotels and a jet airport. The road from the airport to El Chalten is now fully paved and takes less than three hours by bus or car.

El Chalten, nestled below Fitzroy, didn’t exist in the mid seventies. The bridge across the Rio Fitzroy wasn’t there and the broad plain on the other side, now the home of the fast growing town, was absent a single structure. I now refer to El Chalten as the “Chamonix of Patagonia.”

In the seventies we had to wade the Rio Fitzroy and hike ten kilometres into Laguna Torre were we constructed crude shelters to ward off Patagonia’s notorious weather. We had no communication with the outside world and no way of knowing when the next storm would come roaring out of the Pacific Ocean.

There were no stores, motels, restaurants and there were very few people…it was a true wilderness. Any rescue had to be self-implemented.

The equipment was, of course, vastly inferior to today’s gear. We had the best available at the time but the technical hardware, ice tools, boots, clothing, stoves etc. were primitive by today’s standards.

In general, I would say that alpine climbers in the seventies had to be much more self reliant. Keep in mind that we were totally unaware of the vast improvements in infrastructure, communications and equipment that were coming so we could hardly miss them.

Jeff Lowe in 1978 at 21,500 ft. on Latok 1. Photo by Jim Donini

I have never been to Patagonia myself, but reflecting that El Chalten did not even exist when you did the first ascent of Torre Egger really blows my mind. Any other significant changes or details that stick out from that time?

The Fitzroy / Torre massif is now in Parque Nacional Los Glaciaries which in the 70’s existed in name only. There was very little enforcement…gauchos pastured their sheep there and climbers built shabby huts. Now there is strict enforcement and the sheep and huts are gone. The infrastructure throughout Patagonia is vastly improved. In the seventies there were few visitors, now thousands of trekkers and tourists (mostly European) travel to Patagonia by jet and avail themselves of the many hotels, hostels, restaurants, busses etc. that have sprung up in recent years. Interestingly, with a little effort, you can still set forth where no one has been before.

What is your perspective on the current trends in alpinism (and climbing) compared to 40 years ago?

I have always appreciated modern advances that aid my climbing and quickly adopt them. I don’t have the curmudgeon’s stance of deriding how easy today’s climbers have it. Alpine climbers today suffer just as much as in the past….equipment and communication advances just allow them to do so in better style and on harder climbs. Look at the demise of expedition style climbing in favour of alpine style. I believe that I was an early proponent of “alpine style”…in five decades of climbing I have always been in a team of four or less.

George Lowe jumaring icy ropes high on Latok 1. Photo by Jim Donini

Forgive me if you have been asked this before but having a true history with the Compressor Route, what was your take on the decision to chop the bolts by Hayden Kennedy and Jason Kruk?

Cerro Torre is, in my mind, the world’s most beautiful mountain. It deserves more than to have been defiled by the Compressor Route which was so cynically put up by Maestri. If he had climbed CT with Egger in 1959 it would have been near the top in the history of climbing in terms of audacity and style and there would have been no need to come back years latter with a compressor and a virtual army to subdue the mountain with neither audacity nor style.

I am glad that the bolts were chopped but Jason and Hayden should have tried to work with the local Argentinian climbers. In not doing so they were viewed as young interlopers from North America and this created some hard feelings. Hell..the route still goes at 5.11+ A2 which is in the pay grade of many of today’s climbers.

We have talked about Patagonia but not too much about the Karakoram. Can you tell us a bit about your experience in this region and why it keeps calling you back?

Patagonia serves up the most challenging climbs in the Western Hemisphere as does the Karakoram in the Eastern Hemisphere. All of the 8,000 meter peaks in the Himalaya have routes that offer minimal to moderate technical difficulty. Not so for some of the 7,000 meter granitic peaks in the Karakoram like Latok 1, Ogre 2 and the Ogre…they are the hardest peaks to summit on the planet. More subjectively, I also feel that the mountains of Patagonia and the Karakoram are the most beautiful I have seen. Everest is the highest peak but it doesn’t come anywhere near the Latok/Ogre group in either difficulty or physical beauty.

John Bragg on the first ascent of Torre Egger in 1976. Photo by Jim Donini

Looking back at some of your most famous ascents, is there a particular event that sticks out as special to you and what, in your opinion, contributed to that particular trip being more special than the rest?

There have been many memorable climbs…seeking more is what keeps me going. I would have to say that the North Ridge of Latok 1 in 1978 stands out. George Lowe, Jeff Lowe, Michael Kennedy and I were attempting a futuristic climb, in contrast to typical Karakoram expedition style, and we very nearly succeeded…and we JUST made it back to tell the tale.

We took 14 days of food with us and due too the unrelenting difficulties and long storms at the beginning and the end, our supplies had to be stretched to 26 days. If Jeff had not taken ill in our snow cave just below the summit I feel that despite our weakened state and the bad weather we would have stood on top. We turned around with apparent difficulties behind us only a hundred vertical meters or so below the top of the ridge. Even so, we had stretched the umbilical to the limit. The harrowing stormy four day descent replete with 85 rappels will forever be etched in my memory.

In the ensuing years more than thirty teams of expert alpinists, equipped with far superior gear, have attempted to finish the North Ridge. Until the recent Russian climb, no one got closer than 2,000 vertical feet below our high point. I’ve always made the effort to take photos, and these images, spread over more than forty years of photographic technology, will show the viewer the beauty and anguish of the climb.

The Latok/Ogre Cirque. Latok 1 on the left…the Ogre on the right. Photo by Jim Donini

As climbers, we are often driven by the goal itself, but it often it is the people that make a trip memorable! Has there been a shift in your own gratitude for these goal driven experiences, from being a young climbing up to present day?

I once was most motivated by the climb itself, later by where the climb was and now I am most motivated by who I am climbing with. Exploring new alpine arenas with people I enjoy being with motivates me more now than pure technical difficulty which, given the slow but inexorable diminishing of my skills, is a damn good thing.

I want to talk a little about ‘diminishing skills’ because I think it something that will happen to all of us who stick with climbing for our lifetime. What has surprised you about the process of aging and being a climber?

Diminishing skills is relative, I can no longer climb like I did in my prime but I am pleasantly surprised at what I can still do at my age. The first thing I noticed was that it took longer to recover. I can still do a long day in the Black Canyon but I can no longer answer the bell the next day. Remember…it’s not about the numbers, it’s the experience.

There are many out there who would have turned their back on climbing once they were not climbing at the same level as their youth. What keeps you motivated and is there anything in particular that you do to prepare your body for the long haul both before and after climbing?

Climbing is not a sport where you keep score, it’s a lifestyle. Forget the numbers you are putting up and enjoy the gratification that comes with moving freely in the vertical realm. I said earlier that your lifestyle was the only thing you can control in regard to your physical well being. I live in the San Juan mountains in Colorado and I love to do long, solo enchainments of 4,000 meter peaks. I also treat my body better than I did when I was younger. I drink moderately, eat well, hydrate more and get enough sleep. I listen to my body which, since I was never divorced from it, tells me what it needs. Exploring new areas, especially in the mountains, helps me keep my motivation as does the sheer joy of athletic movement over stone.

Prior to climbing, you had joined the army and then left the army to pursue a climbing career. Can you tell us a bit about this experience , why you decided to join the army in the first place and how it has shaped you as a person?

In the summer of 1962 after my freshman year in college I fell asleep while driving and my best friend was killed. I responded, perhaps to punish myself, by dropping out of school and joining the army. Once in I heard about the US Army Special Forces (Green Berets) which specialized in asymmetrical and guerrilla warfare. I took the tests, was admitted and after lengthy training found myself in a Special Forces 12-man operational team based in Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

In the summer of 1964 we were mission training, along with two members of the British SAS, in the mountains of North Carolina. One day the British set up a top rope on a nearby cliff and I was hooked.

My time in Special Forces helped prepare me for life and was instrumental in developing the way in which I have approached alpine climbing. I learned the importance of strategizing, planning, training and (most importantly) the immense value of good partners. In a SF “A Team” you learn to have unshakeable faith in your team members. That trust is based on their expertise and on the intense regard they have for the welfare of everyone else.

When young climbers ask me what is the most important consideration regarding alpine climbing, I unhesitatingly say that by far the most important thing to consider is your partner. While during the past half century I have climbed with hundreds of different people, in all of those years, on forty plus “alpine climbing” expeditions, I can count the total number of my partners on the fingers of both hands.

For anyone who is climbing well into the 70’s, it must feel that the climbing partners keep getting younger and younger! What do you think has led to your longevity as a climber, both physically and mentally?

I thoroughly enjoy tying in with young climbers, they motivate me and remind me of my halcyon days and I think they appreciate what little mentoring I can provide. I also have some older friends, most a decade younger, who continue to hang on.

When asked about longevity I respond that there are three things…genetics, lifestyle and luck and the only one that you can control is your lifestyle. I have never had a bit of trouble with my joints, ligaments or tendons which I somewhat attribute to genetics and I have never been injured. This has allowed me to continue climbing without having any downtime. Downtime, as you age, leads to decline. Continued mental motivation for me is partly based on the discovery aspect of alpine climbing that is so important to me. Discovery can continue unabated as physical prowess diminishes.

With such long career as a climber, there are always a few friends that you lose over the years. Can you talk a little about the loss of friends along the way and the impact it has had on your own life?

Given my longevity and the arenas in which I climb, I have lost many friends and acquaintances in the mountains. I mourn their passing but avoid saying “they were doing what they wanted to do” which I find nearly as trite as saying “thoughts and prayers” after the latest episode of gun violence.

I don’t know what motivates an individual alpinist- but I respect their diverse reasons.

The alpine world is harsh and unforgiving but its siren call is compelling. Those who enter know where they are going. You don’t have to “bury my bones on the lone prairie”…the foot of a mountain will suffice.

Finally, where do you see yourself going this year and what are some of the adventures you have planned?

In December my wife and I will make our annual pilgrimage to our home in Patagonia. You can safely bet that I will poke my nose into some lonely place where no one has been before.

Thanks again for chatting with us Jim! I really enjoyed some of your answers and your perspective on climbing throughout a lifetime! Really looking forward to your presentation on Friday!

On Friday, Oct. 25th, 2019, BCMC & VIMFF present an evening with climbing legend Jim Donini, plus a screening of On The Verge, climbing in the backcountry of Powell River, BC.

Tickets can be purchased online and cost $20.00.