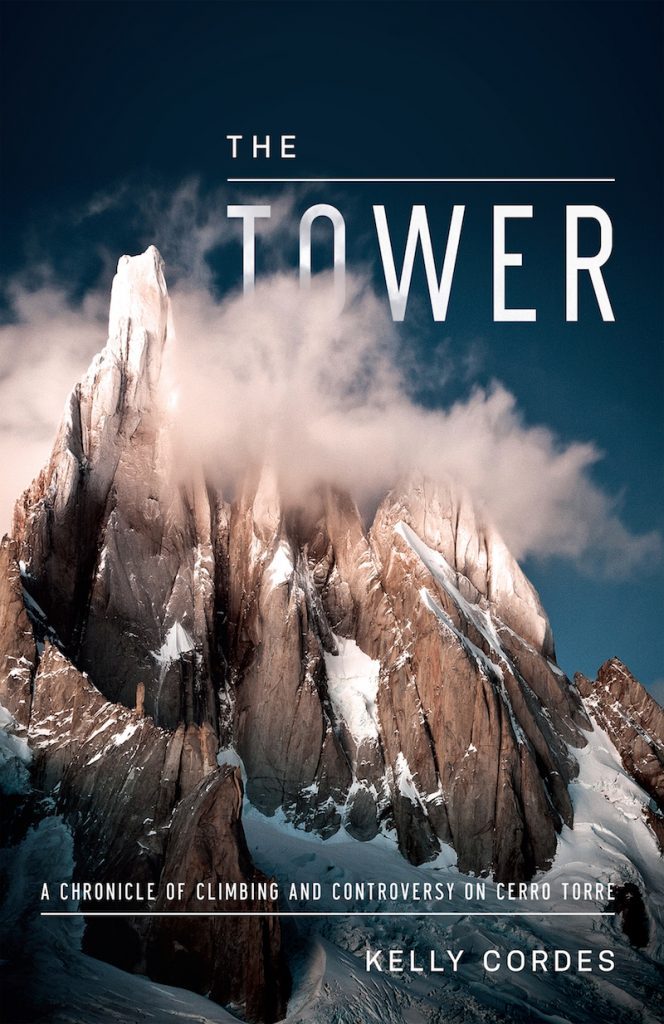

Climber and author Kelly Cordes has established new alpine routes around the world, from Alaska to Peru, and Patagonia to Pakistan. An editor for the American Alpine Journal from 2000-2012, Cordes went on to chronicle the history of Cerro Torre in his book The Tower which won a 2015 Banff Mountain Book Award and a National Outdoor Book Award. Following the completion of his book, he co-authored Tommy Caldwell’s 2017 bestselling autobiography, The Push. Kelly currently lives in Estes Park, Colorado and spends his time climbing and skiing as much as he can.

Kelly Cordes. Photo courtesy of VIMFF ©

We had a chance to chat with Kelly as he made his way to the Canadian Rockies and on to Vancouver. Here is what he had to say.

Thanks for chatting with us Kelly! Let’s start with the obvious. When was the last time you were in the Sea to Sky region and what will you be presenting at the Vancouver International Mountain Film Festival?

I climbed in Squamish for a couple of weeks in September. I try to make it up for a bit each summer, it’s one of my favourite places. I absolutely love it — hell, I’d move there, except I hear Canada’s building a wall to keep us out…can’t blame ya. I’m always psyched to return to the region. I’ll be talking about a mix between my personal adventures and journey, alongside diving deep into the Cerro Torre book project. They overlap in some interesting ways.

I want to get into your book The Tower, which is an awesome book and must have taken a ton of work! The whole process started for you after the bolts had been chopped from the Compressor Route on Cerro Torre. Can you take us back to the moment when you first heard that Jason Kruk and Hayden Kennedy chopped the bolts coming down the Compressor route and what was your first reaction?

I think I primarily felt awe. I had respect and admiration for what they did, alongside fear or concern about the reaction. Hayden was a close friend, and I’d long thought the Compressor Route a lame and senseless installation; at the same time, I’m old enough to be more pragmatic than idealistic at times, which makes life easier, although it’s not necessarily something I’m proud of. I admire the bold and idealistic, and I supported their actions. But I feared it might be a mess.

Back home, we heard the story of the pair chopping the bolts and then a number of people being incredibly upset and thinking that there actions threatened to whole Patagonia scene. Looking back, was this true to some extent?

I don’t think it posed any threat to the Patagonia scene, actually. I’m aware that I might be biased, because I like those guys and I supported what they did. But I also had to be objective, do my research, and listen to those who were opposed, all of which I did for the book. In the end, after things simmered down, I learned of no harm caused by the removing the bolts. There have been many controversies in Patagonia over the years, including ones where people left big messes on Cerro Torre. The irony in this case is that the controversy was bigger (by orders of magnitude) even though the bolt removal left the mountain cleaner, and few, if any, people supported the original installation of the Compressor Route. Yet, that didn’t necessarily mean that people supported its removal, either. Many paradoxes in the Cerro Torre affair.

You talk about climbing not being a democracy, that when they chopped the bolts they didn’t ask permission and they didn’t have to. Can you tell us a bit about this idea and how it shaped some of your ideas or conclusions about the event?

We don’t always like to hear it, but it’s true, and it’s also part of what we love about climbing: for the most part, you do whatever the hell you want. It’s shocking in a sense, and non-climbers especially can’t believe it. But in most parts of the world, it’s true. It took me a little while to come to this realization as well. People leave rap anchors wherever they need to, place protection bolts on new routes, and so forth. Nobody gets, or needs, permission to do so. Climbing is entirely self-regulating, and sure, we have our controversies, but it’s astounding that it works as well as it does. As the world grows, more people get into the sport, public land issues increase, and so forth, I suspect that regulations in some areas might increase. We’ll see. But as to the Cerro Torre issue, sorry to be cheesy but I’ll just quote my book, where it’s stated as well as I can put it. From Chapter 31:

Some of the arguments sound perfectly logical at first, like “they didn’t have a consensus” or “they needed the approval of locals.” But they’re essentially variations of the straw-man argument, where an inherently false notion is held up as truth, as something legitimate, that was subsequently violated. Here, the false notion is that climbing is some kind of democracy.

To the outside observer, or even the climber who hasn’t thought it through, it sounds like a good idea. Democracy always does. But step back for a moment and you realize that democracy doesn’t exist in most areas of our lives. The farmer doesn’t require an Internet vote before he plows the field. The surgeon doesn’t consult with the hospital cafeteria on operating techniques. The football coach doesn’t survey the local fans and community before calling plays. None of these are exercises in populism, and neither is alpine climbing.

That’s the hardest thing to take: that your opinion doesn’t matter. My opinion doesn’t matter. Nor the baker’s, the schoolteacher’s, or even the rescue volunteer’s.

We can complain, talk, discuss all we want, reinvent history and pretend that climbers need to check with us, or with somebody, anybody, before conducting unilateral action. But they don’t. To paraphrase a statement from the illustrious Yosemite climber John Long: The vanguard doesn’t give a damn what you think.

What brought us Maestri brought us Kennedy and Kruk and every single climber between, before, and after. Sometimes we don’t like what they do, but it’s the price we pay for our self-regulating system.

“For me, climbing is freedom—the maximum freedom available to anyone. And this freedom should not impose on the freedom of others,” non-local Cesare Maestri said in a 1972 interview.

“Climbing is not a democracy. It never has been. That’s one of the things we love about it. Climbing is about freedom, and just as Maestri scarred Cerro Torre when he put in all those bolt ladders, Jason and I removed about 120 of his bolts on our descent,” non-local Hayden Kennedy said in 2012.”

Kelly Cordes. Photo courtesy of VIMFF ©

This whole story unearthed a wild history of Cerro Torre for you, leading to the investigation of stories and pictures regarding the controversial first ascent. Whether or not there was a lack of truth in the first ascent, it begs the question: Why do you think climbers lie?

Because climbers are human. Humans lie. We have lied since the dawn of time and we continue to do so, for reasons often poorly understood. I don’t know why, exactly, but people often lie to make themselves feel better, or to make themselves look better to others. I’m certain that nobody loves climbing more than I do, but at the same time I’ve long thought it absurd that we somehow think that being a climber makes us inherently superior human beings. Of course, most people would overtly acknowledge that they don’t think that. Yet climbing still has a bizarre, longstanding code of always taking another climber at his or her word. It’s ludicrous, yet tribal, and so inherently human. The difficult question follows: So what, if anything, is there to do about it? Do we care enough to require concrete proof or are we OK with living with this fact that climbers are humans, and not necessarily supreme humans, and therefore climbers sometimes lie.

We are talking a bit about Maestri here, and I am sure that lying about something in 1959 is different than it is today. How prevalent do you think lying is in climbing culture today?

Uff, I don’t know. I really don’t, and in my head I can construct hypotheses as to how or why it might be more or less prevalent today than in earlier years. As I babbled about above, no doubt lying exists today. It always has. I mention some of this in my book, including my own encounter with people lying on a large scale, about a very major ascent (we were trying for the same line, on a peak in Pakistan). For twelve years, I was an editor with the American Alpine Journal and I rarely encountered concrete cases of people lying. But you’d stumble upon iffy things, or later learn of shady practices like incomplete reporting, or lies by omission. It never seemed to happen a lot, at least as far as I could tell. But as a natural skeptic and critic (hey, everybody has a specialty in life, right?), I suspect we get duped more often than we think. Both in climbing and in life.

Kelly Cordes. Photo courtesy of VIMFF ©

Writing a book about Cerro Torre, and everything that comes with it, sounds like a detective novel, trying to figure out what really happened in these moments that happened years ago through oral narratives and pictures. What drove you to find the truth about this story and what was it like hunting people down and unearthing the stories surrounding Carro Torre?

Yes, absolutely. I’m not sure what drove me. I just got into it, and then couldn’t let go until I uncovered every stone. Much like many of the climbers I wrote about, I became obsessed, and I wanted to do it right, to be fair, and part of both of these things means exhaustive research and not half-assing any of it. I ended up doing in-person interviews in seven countries, and my selected bibliography contains 256 entries (many, many more helped inform my thinking). It was a wild and intense journey.

Throughout the process, you must have spent a lot of time in El Chalten. How has the scene in Patagonia changed over the years? Has it gotten more crowded? Do people still come as prepared as they had in the past? Does it still hold the allure and magic that you first experienced there?

As with most beautiful places, it has become far more crowded. This is natural, and though everybody complains about it, intellectually it’s hard to gripe. How can you fault people for coming to enjoy the same thing that drew you there? From what I’ve gathered, more folks indeed venture up there unprepared. I think that happens with any form of growth. Problem is, with alpinism it can be deadly and it often is.

I haven’t spent a lot of time there myself, curious as that sounds. Only two trips to the Chaltén region and a ton of research. Much as I hate to admit it, the allure and magic seem slightly diminished to me when a place gets more crowded. Again, not faulting anyone, and I recognize that if I’m there, too, then I’m also part of the problem. And at the same time, it’s amazing that so many more people get to experience the place. It truly is special.

Kelly Cordes. Photo courtesy of VIMFF ©

I really like your concept of Old Patagonia and New Patagonia. Do you think something has been lost in Alpinism through technology and infrastructure or do you think it is as wild as ever?

Most certainly something has been lost. But is that all bad? Things are lost and others are gained. The emergence of weather forecasts are the perfect example. I have a couple of chapters directly addressing this topic, including interviews with those who have climbed extensively in both Old and New Patagonia (as I call them). Fascinating perspectives.

Recent media has portrayed the exploits of going to Patagonia and crushing these routes as somewhat of an easy task (Alex Honnold/Tommy Caldwell Reel Rock) but they are really not easy. Do you think that type of media has an impact on people coming prepared vs. not prepared to Patagonia?

Oh, probably. Much as climbers like to brag that they aren’t influenced by anything, we are all influenced by media, especially in our hyperconnected world. But how much? And is there an obligation to not celebrate some cutting edge climbs, even if they seem easy for top climbers, in the interest of protecting the ill-informed from themselves? I don’t know. Media hype shouldn’t mislead but folks also have a responsibility be prepared. It’s a tough balance.

How did you first get into climbing and then how did that lead to alpinism and that drive to suffer in the mountains?

While in grad school in Montana in the early 90s, a friend took me ice climbing one day. That was it. I was hooked, and knew what I wanted to do with my life. I’d already fallen in love with the mountains and was an avid skier, trail runner, and mountain biker, and so I think my climbing interest naturally gravitated toward alpinism. The suffering, geez, not sure. It’s mostly from stupidity mixed with ambition and laziness. I hate carrying a heavy pack and often deluded myself into thinking we could do big routes faster than we could which is a recipe for suffering. The irony is that the more you do it, the more you’re exposed to dangerous situations but the better you get at it.

What is it about these adventures that just grabs at the core of living?

People have tried to answer that forever. It’s difficult to articulate but I think the allure of the unknown draws upon deeper elements of ourselves extending beyond our everyday existence, and when we embrace the unknown in wild places we also embrace an instinct both primal and beautiful which allows us to expand our inner worlds. All told, it makes life feel extraordinary.

As you get older, are you still capable of the same amount of suffering you did when you were younger?

No, I’m not. It’s been challenging to accept but in my mind it doesn’t have that bizarre, somewhat twisted appeal that it used to. The flip side—related to some things I mentioned above is that I’m probably better at it than when I was younger. But I don’t want to suffer, it kind of sucks. Even though I used to love it.

There is not a lot of information about your own climbing online but you spent time in Pakistan before Patagonia. Can you tell us a bit about this time?

My Pakistan trips are some of the strongest experiences of my life. I built up to them, cutting my teeth climbing in Montana and then many expeditions to Alaska and elsewhere. But Pakistan and the Karakoram Mountains are on another scale. The country is just so different. The people are amazing, warm and hospitable (for those who spend too much time watching cable news, they aren’t all Taliban, any more than all Americans are gun-toting lunatics), and the Karakoram makes everything else – even Patagonia – look like child’s play. The peaks are so big, the scale so unfathomable, and you’re so far out there it’s like being on another planet. My first trip to Pakistan, in 2004, when Josh Wharton and I climbed a new route on Great Trango Tower in lightweight alpine style (I’ve called our approach “Disaster Style”), was the greatest adventure of my life.

Finally, looking back and with the book finished, what is next for you?

Lots of climbing. After The Tower, I co-wrote Tommy Caldwell’s memoir, The Push. Since then, I’ve been writing less (I have a full-time job with Patagonia, too), and climbing way more. But I’m getting the itch to write, and have some projects in mind. We’ll see if I can pull myself away from time outside and actually do it, though – writing is hard, infinitely harder than climbing.

Thanks again Kelly. Really looking forward to your presentation this Thursday!

Thank you! I’m really looking forward to the festival, and being in the region. I love it there.

Kelly Cordes. Photo courtesy of VIMFF ©

Tickets for Kelly Cordes this Thursday at the Vancouver International Mountain Film Festival can be found here.

—

Our content would not be possible without our sponsors Flashed Climbing, The Hive Bouldering Gym, Climb Base 5, Climb On Squamish, the Vancouver International Mountain Film Festival, Kilter Grips, Bolder Climbing Community, and Gneiss Climbing. Be sure to give them some love!!