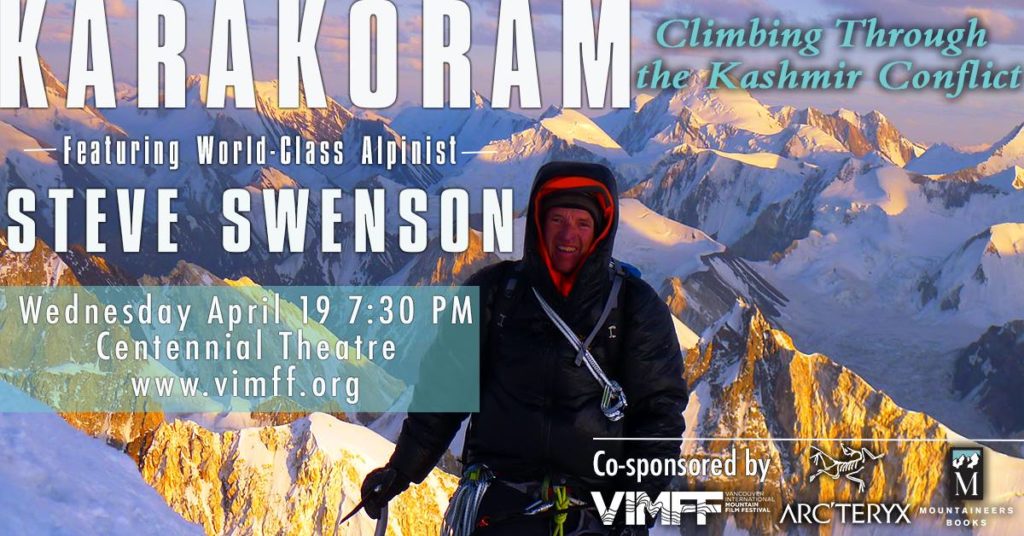

On Wednesday, April 19, The Vancouver International Mountain Film Festival will feature Steve Swenson, American aplinist, as he explores the nature of high altitude, alpine climbing, the complexities of remote expeditions, the geo political workings of Kasmir, as well as his passion for the cultural communities in this region of the world. The presentation will be followed by a Q & A where four experts will bring their unique perspectives to the Kashmir Conflict and how it effects climbers and trekkers.

With a number of ascents under his belt, including the second ascent of the North Face of Mount Alberta, in 1981, the first ascent of the Northeast Face of Kwangde Nup and Mazeno Ridge on Nanga Parbat in 1989 and 2004 respectively, and oxygen-free ascents of K2 and Everest and Steve Swenson is no stranger to adventure. Now retired from Engineering but still climbing, Steve has taken the time to reflect back on his experiences in the Karokoram, as well as the changes that have taken place in the region over the past four decades. Squamish Climbing Magazine had the chance to catch up with Steve before his presentation on Wednesday and here is what he had to say.

First off, thanks for chatting with us. You will be presenting in North Vancouver on Wednesday. Can you tell us a bit about what you will be talking about that night and how it all came together?

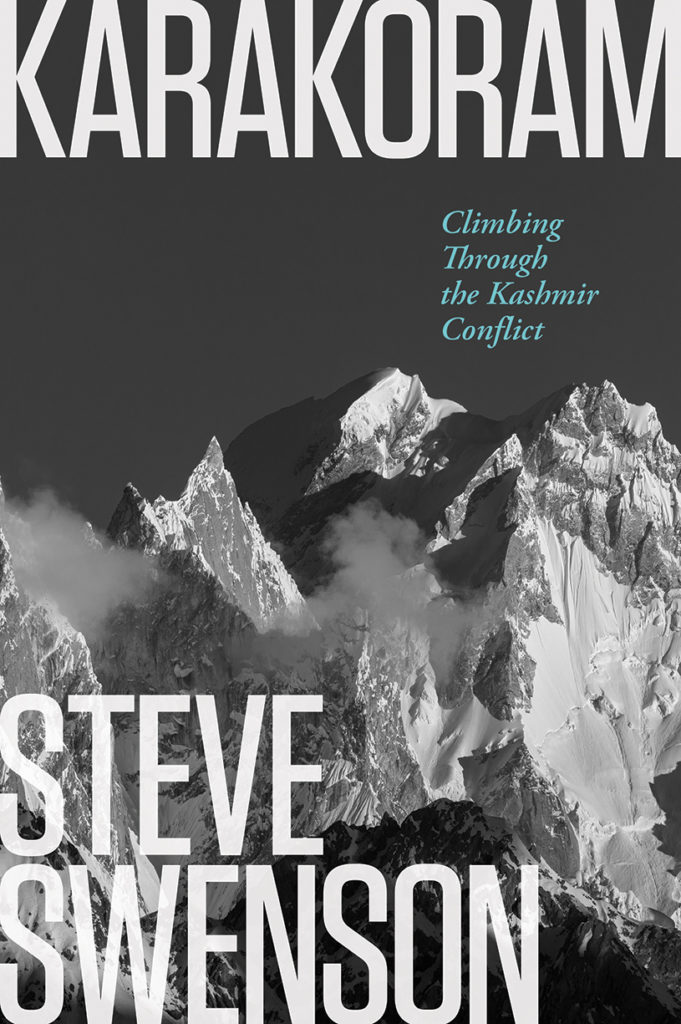

In this presentation, I will talk about the overarching theme in my book of – what it took to learn how to climb big mountains – how this long and frustrating apprenticeship eventually resulted in several successes – and then passing on this knowledge to a younger generation of climbers. Through the lens of an expedition climber I will also talk about my experiences with the local people and the region that dominated by border disputes and political violence.

Steve Swenson. Photo courtesy of VIMFF ©

You recently wrote a book about climbing in the Kashmir Region and some of the experiences you had in that region. What was it like diving into writing down your adventures and experiences?

After coming home from all these expeditions over the years, I felt like I had been too busy with my job and my family to think about what I had learned and what these experiences meant to me. I had a professional career as an engineer where I spent a lot of time using the left side of my brain. I decided to take the opportunity to retire and spend more time exploring the right side of my brain by writing a book. I hope that writing this book has helped me to become a more well rounded and thoughtful person.

With everything you have going on, was the writing process difficult or did it all just come flooding back once the pen was in your hand?

I had a good background in my work as a consulting engineer with writing reports for both technical and not technical audiences. But my book is creative non-fiction which is all about “show, don’t tell”. All my previous writing had been to tell the facts about infrastructure projects and financing. I had to learn how to do a different kind of writing for my book that was much more descriptive and probed the feelings and reasons for what we were doing.

Looking back years later, are the experiences you had as clear as ever or have you forgotten some of what you experienced?

I had journals that I kept for all the expeditions in the book and without those I’m not sure if I would have been able to complete this book. They were the basis for my initial drafts of each chapter. The problem with many of them was they were pretty factual in nature just listing who, what, where, and when. I had to read between the lines and go by my memory to have a complete story.

Any chance you deleted the memories of all that ‘type 2’ fun?

I tried not to. There are some pretty harrowing stories in the book of situations I would never want to repeat.

I am not familiar with the Kashmir region at all and don’t want to pretend that I am but what was it like climbing in the region after 9/11 and what kind of changes did you see in the region?

There was a drastic reduction in the numbers of climbers and especially the numbers of trekkers in Pakistan after 9/11. The main changes after 2001 that effected security came in the years after 9/11. The USA supported Northern Alliance pushed the Afghan Taliban out of Afghanistan after 9/11, but they resettled in the tribal areas in Pakistan just inside the border. These militant groups spilling out of the tribal areas in Pakistan into other parts of the country are the source of all the security issues in Pakistan right now.

For climbers who continue to push themselves in that region, or any region that has experienced political conflict, what advice would you give them as they interact with different communities while completing objectives in the mountains?

Do your homework and find out where all the bad people live and operate and then don’t go even close to those areas. The mountains where we go in Pakistan are isolated from the internal political violence in the country so it is safe to go there. But I will not take the Karakoram Highway from Islamabad to Skardu to get to the mountains now because it goes through and is adjacent to areas populated by people who could cause us harm. Now we wait in Islamabad to take a flight to Skardu or Gilgit , even if we have to wait for several days because of unsuitable flying weather.

Did you ever experience difficulties yourself travelling the highway or run into groups of people that were on the shady side of things?

I have not been robbed or experienced a scary incident on the KKH personally but I have heard of others that have been robbed. The section of the KKH between Besham and Chilas has been sketchy for a long time. Bandits have rolled rocks onto the road and robbed vehicles. We haven’t travelled that section of the KKH at night for many years for that reason and now I won’t go at all. One of the main concerns I have is there are numerous checkpoints along the KKH where they make you get out and show your permit and record your passport # and nationality into a log book. The log book just sits there in the open or in a tent or shack for everyone to see. We are pretty much announcing to the world that a van of Americans is heading up the KKH. All someone would need to do is phone ahead to their buddies and they stop your vehicle on a less populated part of the highway and kidnap everyone. It would be a nightmare for your family.

Being so motivated in multiple areas of your life, how do you find balance between work, family and climbing objectives?

Over the years that was a difficult balance and now that I’m retired and my kids are all grown up I’m not sure how I did it. Mostly I had to be pretty focused on what I’d spend time on and then stay disciplined with my training and climbing so I would be in shape for it.

I wanted to chat a little about being the President of the American Alpine Club. What was it like being responsible for such a reputable organization and did you feel that responsibility with that title?

I have a long history with the AAC going back to being a board member in the late 80’s and early 90’s. There was a group of us who wanted to modernize the AAC so it did a better job advocating for and including all American climbers. I felt like I was in a good position to help move the change process along. The old guard respected me for the climbing I had done and my organizational/consulting capabilities and I had enough of a relationship with the younger climbers to bring their perspective into the process as well. In the end, I think we moved the ball a long ways but the world keeps changing so there is always work to do to stay relevant.

Why do you think these organizations play an important part in shaping climbing culture?

We need to have advocacy organizations for our sport and these alpine clubs are important to the extent they are able to help the community go climbing and to help preserve the places we do that. These clubs need to prioritize their resources on the projects and programs that will best serve that purpose. It’s very important that active climbers volunteer to get involved in these clubs to make sure they are delivering the things that will keep them stay relevant. If the oversight for these clubs is a small group of people who are not active climbers, then they won’t be able to serve the entire community very effectively.

Your climbing experience has spanned almost four decades and with the passing of time, there must have been many changes from being a younger climber to still pushing yourself as the years went on. In your opinion, what are the biggest changes in the climbing community over the years and where do you see that going in the future?

Climbing has become segmented into several subsets of activities like gym climbing, bouldering, sport climbing, trad climbing, waterfall ice climbing, alpine climbing, and expedition climbing. Climbers today might participate in only one or two of these subsets. When I started climbing we tried to do all these things, but we were not very good at any of them compared to the climbers who specialize in one of these subsets today. Climbers today are more skilled in the activities they specialize in, but there can be gaps in their understanding of the entire mountain landscape if they decide to head into the alpine. In the old days, we had some understanding of the entire landscape, but when it came to climbing skills it was easy to be a mile wide and an inch deep. I think this specialization will continue and organizations like the AAC will learn how to help the community fill the gaps created by a more segmented learning process. I think that in the future climbing education will be more seamless and then people will be getting after it even more than they do now!

A number of your partners throughout the years must have stopped climbing but you continued. How did you stay so motivated and how did you cope with that community changing?

I love climbing and want it to be a lifelong activity. Like anything, the world changes and people change so if you can’t adapt to those things you are dead in the water – and this applies to everything! I like to see things change because it is usually part of a creative process that is helping us get better. Seeing the community do amazing things we couldn’t have imagined 30 years ago is pretty inspiring.

I want to talk a little about training because you were training much earlier than the rest of the masses. How has a good training regiment influenced your outlook on some of your objectives?

I was a distance runner in high school and kept doing that in college. Being coached in an endurance sport when I was young enabled me to apply that discipline to the climbing I wanted to do. Back in the day when climbing was a fringe sport and organized training wasn’t common, the people who had a good program stood out. With the gyms and now even with the work that some folks like Steve House is doing we have training designed specifically for climbers. This has really helped push the standards up.

Do you have any mental strategies that you use to push through times where there is a lack of motivation?

I try to think about what the people who inspire me would do. WW?D – just fill in the blank.

What does training look like for you know and do you still have objectives you would like to accomplish looking towards the future?

For high altitude stuff that requires some good cardio training, I spend more time now on high volumes of low intensity training. I do this partly because the experts are all telling me that, but also as I get older I need to take a more measured approach to training or else I get injured or I’m tired all the time from overtraining. You can get away with some of those mistakes when you are younger. For strength training I’m spending more time in the bouldering gym. There is lots of padding and it forces me to me more dynamic and powerful than roped climbing (which I also like to do).

What is it that you love most about life in the mountains and what keeps you returning year after year?

All these climbs over the years were just the inspiration to live a life of exploration and adventure that I wanted to have when I started climbing at age 14. What I didn’t know at that age was these experiences would instill a set of values like partnership, fortitude, stewardship, personal responsibility, compassion, acceptance, creativity and the list goes on… In the end these are the things that are most important and the mountains, in some form or another, will always be one of my major sources of inspiration for self-improvement.

Finally, any advice for those climbers hoping to push themselves well into the 50’s and 60’s?

When you get to this age you should understand it isn’t about how hard you climb, but being smart about how you take care of your body. We all want to be able to keep pushing ourselves, but every day you come home without injury is a victory. People ask me, “What are your projects for this year?” I usually tell them, “Not to get any worse!”

Thanks again Steve. We really appreciate your time and are very much looking forward to Wednesday night.

For tickets to Wednesday nights event, please visit the VIMFF website.