As a publication, we have never crowned a Canadian climber of the year but looking back, we probably should have. There were a number of amazing contributions by Canadian climbers this year around the globe and some of their efforts are very impressive including Amanda Berezowski’s send of ASDATO (5.14c) at Horne Lake, Evan Hau’s long list of first ascents including Neanderthal (5.14b) and Cobalt Gecko (5.14c), and Sonnie Trotter’s variation to North America Wall, Pineapple Express (5.13b).

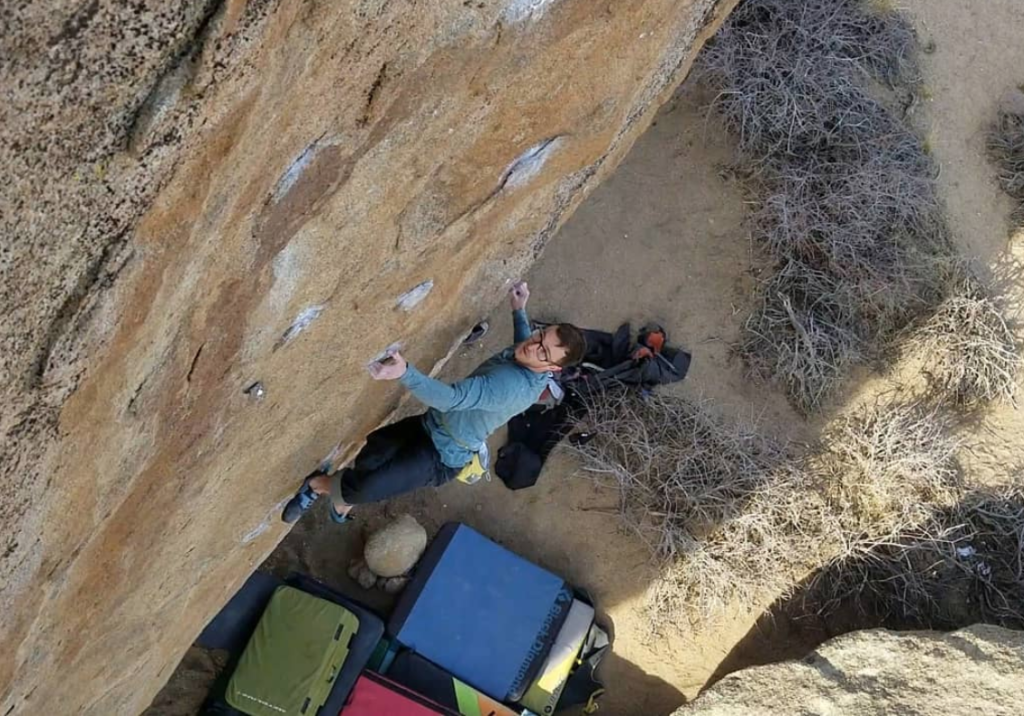

After looking through the accomplishments, for us there was one climber who stood out from the rest and that was Edmonton-based climber Miles Adamson. Miles had an impressive summer in the Canadian Rockies, sending Honour and Glory (5.14d), establishing one of Canada’s hardest multi-pitch climb Don’t Rock the Boatswain Extension (5.14b), establishing a new zone in the Rockies with the help of Scott and Marc Eveleigh, Zach Watson, and Matt Hendsbee, putting up Rootin Tootin Cowboy Shootin (v13), a highball in Red Rocks Canyon, and then ending the year with an ascent of Ambrosia (v10) in Bishop, CA.

We had a chance to sit down and chat with Miles about all his experiences this year and here is what he had to say.

First off, congratulations on finishing off 2018 with a send of Ambrosia! Let’s start with Ambrosia because it is the freshest right now! People may or may not know but your goal for Ambrosia was to make a ‘ground-up’ ascent without any rehearsal of the top of this problem.Thanks so much. I really want to make a ground-breaking highball ascent and one idea I’ve always had was to do Ambrosia from the ground up. It has been repeated quite a bit, so there is a lot of footage on it. This makes a ground-up ascent a LOT more feasible compared to a ground-up on-sight or first ascent. The top is a 12c/V3, and there were no insecure moves. Flashing a gently overhanging 12c is much more straightforward than something like a slab. I know I’m strong enough to pull through 12c crimping virtually every time, which made me feel like a ground up ascent was well within what I’m capable of.

So what did the process look like for you?

I studied the route really hard, watching every video on it many times. I drew out on paper every hold on the problem, then mapped out on it what everyone did as a hand sequence. On my previous trip in February 2018, I tried it for the first time. I actually flashed all the way to the heuco. That is the route’s defining hold, basically seen as the point to either back down or go to the top. I did two moves more, but my hands were cold and I was too pumped so I hopped down. After that go, I was actually pretty sure I would just do it second try. However, I got to the same move and hopped down again. Then again. Then every try on every other day too.

The move I got stuck on was this strange rock-on move on a poor foot which is way too high. The right hand you are moving from was so much worse than it looked in videos. This is mostly because people have done the move tons of times on top rope, so its super dialled for them. I got to the move five more times that trip, several of which I fully committed and took an uncontrolled fall. I took around eight 25-foot falls from that move in total. From those I got jumpers knee (tendonitis) in both knees. I couldn’t fall bouldering for several months, and down climbed literally every problem in the gym for around 6 months.

You ended up deciding that it was safer to practice the top on a rope before your ascent. How did you make this decision and what was that like to really come to terms with what was really a safer decision?

During the recent trip, December 2018, I got to the same move three more times. I made basically zero progress, even though I felt much stronger and could stay a while on the holds trying to figure it out. From those falls, I could already feel my knees hurting a bit and was doing physio during the trip. After the last fall, I figured I couldn’t fall again from that high. Also, doubt was really sinking in about the top sequence. They say it’s V3, but I’m struggling so much with this one move that isn’t supposed to be super hard. What happens if the top is harder than I think as well? I decided then to top rope the route. I found new beta for the move I was struggling on very quickly.

We had talked earlier in the year about your relationship with the late Marc Andre Leclerc and his thoughts on Ambrosia. Did that make this ascent special in some way?

The last contact I had with Marc was his facebook comment on my Ambrosia post in February. I shared the video of my flash attempt and he said “Be careful. But would be proud as fuck.” It definitely would have been more special if it was still ground up. He would have loved that, as such an adventurous person. I would have dedicated it to his memory if it was ground up but I don’t think just repeating it normally was big enough. I still plan on finding some mega climb to dedicate to him.

I want to talk a lot about this past summer because it seemed to be a big one! First off, you had the chance hang out with Adam as he tried to flash Honour and Glory and at the same time, you were also gunning for the second ascent. What did you learn from hanging out with Adam and watching him engage in the process?

Man, Adam is obsessed! The entire hike, every hike, he would talk about climbing. Not just the project at hand, but about all sorts of routes, memories and recent news. It makes sense that the person who loves climbing the most is also the best at it. It surprised me how chatty and personable he is, considering how he is portrayed in climbing films.

The main thing I learned was how to do training maintenance on an extended trip. I didn’t realize just how much he climbs indoors on an outdoor trip. Maybe a third of the time is actually just training, to keep in completely peak shape. Doing the same definitely helped me get the edge to send.

You had the chance to really pick Adam’s brain about training and performance and I am wondering if you could share some of the things you learned from him with us.

The main thing above all else is to keep training sessions a normal length. Adam trains like six hours a day, but NEVER does more than three hours in a row. He says that by splitting up his sessions into morning/evening, he actually recovers enough in the middle of the day to have a great second session. This way, he never tears his muscles so badly that he needs an immediate rest day. When doing sessions longer than three hours, he found that he would be so sore and injury prone that he had to take one or even two days off.

Right before doing Honour and Glory, I did exactly what he said. I went to Elevation Place and did sets of 4×4’s and circuits twice a day for four days in a row. Then I took 2 days off and sent the very next day. I was very surprised at how good I felt during the second session of the day.

Obviously, it’s not very realistic to train twice a day as a normal climber. But I think we can definitely take away from this that it’s much better to increase the frequency of your sessions compared to the length of your sessions.

You ended up making the third ascent of Honour and Glory, which was later downgraded from 15a to 14d. What was the process of throwing yourself at this route like?

I’m already pretty used to projecting, so it didn’t really feel like much of a grind. I’ve actually had some much longer projects in Squamish, which took multiple seasons. I really don’t mind measuring my progress in such small steps, such as climbing the route with 3 falls instead of 4.

It was actually very exciting to start off with. I kind of assumed I would find some sequence I couldn’t do, or could barely do and could never do from the ground. That never came, and I got to the anchors knowing I could definitely send the thing.

You were pretty vocal about this route not being 5.15a before finishing it off. Reflecting back, did that enhance or take anything away from the experience?

No, I didn’t really care. I just said what grade I thought it was. The breakdown of the route never made sense to me for a 15a so that’s what I said. Dreamcatcher (5.14d) actually has much harder moves, and the rest on the rail is far worse than both rests on Honour and Glory. Dreamcatcher is much shorter so you expect it to have harder moves, but still I always thought Dreamcatcher was harder. The funniest part of the whole grade thing is that Ondra said the line would undoubtedly be 5.15 if several pieces of scree were not glued onto the wall to make a crux much easier.

So…seeing Ondra and climbing Honour and Glory. We still haven’t even covered half of the things you did this summer in the Rockies. Can you tell us a bit about your exploration bouldering trip behind Protection Mountain and the crew that accompanied you? Was the hike a total killer or did it make it that more special and Next year, do you plan to go back?

We went as a group of five. It was Scott and Marc Eveleigh, Zach Watson, Matt Hendsbee and myself. Scott is THE guy for Rockies bouldering. He loves going out to random boulders he found on google maps satellite view. This particular area looked just massive from the satellite images. The area is behind Protection Mountain. To go back there, you must basically summit the mountain and hike into the valley behind it. It was an insane day. I think it was close to twenty hours car to car. Clearly there were hundreds of boulders of a climbable size, with some house sized boulders sprinkled in there too.

Him and Matt hiked out there with no pads to check it out. They climbed a couple easy things without pads, took some photos and showed them off. To everyone’s surprise, the boulders looked incredible. In the Rockies, there is a very good chance that random rocks you see in the distance are unclimbable choss.

I think for about 6 months straight, every time I saw Scott he would open up his phones photo gallery and be like “but did I show you this one??” and show me every boulder again. Clearly they were amazing and Scott organized the trip. Since it’s in Banff National Park, you need a permit to camp. Scott got us probably the first backpack bouldering permit of all time, and we were set. Usually those kinds of climbing permits are for alpine objectives.

To get crash pads up there, Scott Marc and Zach had to strap the pads to the back of their backpacks. So, they had a full bag of 30lbs or so, plus a crash pad hanging off the back. I just had a backpack, but it was full with heavier things to be 50lbs. This was definitely easier than the crash pads. On the outside of the bag the pads move your center of gravity way behind you and you get blown around in the wind.

With all the gear, the hike in was nine hours. It took about five hours to get to the treeline on a good trail, and from there we summited a ridge on a scree slope. The scree slope was two full hours of steep uphill. We rested for an hour, then descended into the valley behind.

The hike actually made the trip really special, not just because it’s really out there and crazy but because of how remote and beautiful the area is. Still, I’m surprised people bother backpacking without a climb at the end of the hike, but I almost understand it now. We will probably go again next summer and I hope to send the project I opened, the best steep crimp line I have ever seen.

The pictures just look awesome but I couldn’t help but thinking if you guys could have taken a helicopter in there!

Helicopters can’t land in the national parks under normal circumstances, only for emergencies. It might be possible to get a permit, but it would probably end up being more expensive than it’s really worth.

Is the crimp line you speak of worth going back?

Yes, assuming I’m at a peak in my training. There would be no point if I’m not as strong as possible.

Okay and now we need to chat about Don’t Rock the Boatswain Extension. Can you tell us a bit about the climb? What was the process like for you developing such an extensive route?

Don’t Rock the Boatswain is a route that Zach Watson and I bolted over the course of several years. Bonar McCallum was the one who walked us into the canyon for the first time. The area feels really intimidating to walk in to. The wall towers over the end of the hike on all sides, and are ten pitches tall or more everywhere you look.

The feature that stuck out to Zach and I was the roof capping the dead center of the wall. The roof was so large it made it so we couldn’t bolt on rappel, we would be stuck in free space. We bolted the route on lead, ground up. Most of the bolts we placed from free stances, and invented our own way of doing so. The drill would be on a sling around your shoulder. The bolts would be on the quickdraws your harness. You literally just grab on to something, grab the drill and drill a hold while holding on. Then once the hole is drilled, blow it out and take a bolt off your harness. Shove it in the hold so it stays by itself. Then take the hammer off your harness, pound it in, and clip and take. From there, we just tightened the bolt while weighting it from the take. It didn’t seem to matter that we were weighting them. On-sighting with the drill was very hard and dangerous, since we also had to clean rock as we went or just avoid it to be cleaned later.

The route ended up being pretty hard before the roof and it took us many years of off and on just bolt up to its base. Up to the base of the roof is the original line that we sent and called 5.13-. The roof we left open as a project. Every pitch is 5.12- or harder. On the 5.13- pitch, I tried to put a bolt in off of a skyhook. As I pressed the drill in, the outwards force ripped the block my hook was on off the wall. The block hit me in the helmet and I took a twenty-foot lead fall with the drill out in my hands.

Zach had a habit of just dropping the drill on to its leash when he finished drilling, instead of clipping it somewhere. I think twice he dropped the hot end of the drill bit into his leg, giving him a severe burn. Zach also found out the hard way that if a drill bit burns out, it no longer drills the correct size. The bolts don’t fit into the smaller hole, so he would be way above his last bolt super pumped just hammering and hammering trying to get it in. Any bolts we mangled are still on the wall, either Zach or I definitely had a fun time with each one.

Eventually we got to the roof and I bolted the first half up an obvious weakness. A flaring roof crack, at the back of a corner feature. I brought cams hoping to find a piece or two to put a bolt in from, but there weren’t really any placements. The climbing was so hard I was only going bolt to bolt. I would take as high as I could, then put a bolt in above my head. After not too long my back hurt too much to continue.

Zach then went up and did the same, but was worried what he was bolting was near impossible to climb. I told him fuck it just throw bolts in to the top, we can tweak the bolt positions if we have to later. I never even tried what Zach bolted that day, we just went down satisfied that there were bolts to the top of the wall.

I returned in the summer of 2018 to actually try the extension for the first time, and figured out a sequence that goes without moving any bolts. The pitch is 5.14b, and the final boulder of the entire multi-pitch is a compression V10. Since the roof kicks back so much that you see the entire wall sweeping down below you. The exposure is just amazing and so is the route. It’s really sad that so few people have been up there to experience it as well. I think about the drone footage of someone cutting their feet on the roof with the entire canyon below… I hope one day someone makes it happen.

What a crazy summer! Were you working the whole time as well?

I was working park time at Vertical Addiction. Also I can work remotely for Hi-Q design in Edmonton. I only worked enough to sustain the climbing life, I was practically climbing full time.

In usual circumstances, you are not a full time climber, but rather, have a job and other things going on. What is it like to balance everything out and give some really tough routes your very best?

I don’t actually balance everything very well! I have quite a but of debt to my parents for a car and living expenses. I also still live with them. If I really wanted to focus on a career and money, I definitely would be out in Eastern Canada. It seems like that’s where all the engineering jobs are. But that would take away from my climbing too much to bear. I can be an engineer at almost any age, but until I’m maybe 30, I’ve got way too much to climb. I just can’t do that out East, since I don’t care about competitions right now.

Let’s talk about competitions for a minute. You pretty psyched a couple years ago but they have now taken a bit of a backseat. Did anything change?

Yes, the setting changed. Bouldering competitions used to test all sorts of skills and physical limits of climbers. Things like hand strength, power, power endurance and fitness really mattered. Now the complete list of boulder competition skills are:

Standing on volumes

Jumping off volumes

Jumping to volumes

Mantling off volumes

If you think I’m exaggerating, the last major competition I went to was AB bouldering provincials last year. Only two holds in the Men’s finals round were attached with a bolt, and they were footholds for a dyno to a volume cluster. Every single other “hold” in the competition, apart from like 4 screw-ons attached to a volume, was a volume. If bouldering competitions were actually climbing, I would compete again. I watched the world championship men finals round and it was a joke, every single boulder started with a low percent volume dyno. Then on all four you either dyno or mantle from that volume cluster to the finish volume.

The entry fees and memberships have also went up a lot in price, with the number of events lowered. If I really wanted to spend 1000’s of dollars to stand on volumes, I would buy a volume and stand on it.

Do you think the comp scene has changed dramatically since you were younger and what do you think about the direction things are going?

Apart from the setting, the comp scene used to be the same group of friends who meet up and climb. Of course, people took it seriously, but it was much more fun vibe to it. That was especially true at Tour de Bloc. Now it’s extremely serious. Coaches will appeal against you instantly if they think they can get an extra fall on your scorecard. Every competition has the same rules as a world cup. That means less people in finals, and finals is a very short round because of all the time rule changes. They changed the time limits in both bouldering and lead to force events to be a fixed time, to fit TV slots better in the Olympics. It is much more common to time-out on lead routes now because of how short the time limit is. I could also rant about how stupid speed climbing is for several hours, but many people already hate speed climbing. Except speed climbers.

I say, fuck the Olympics. Why should every competition climber in Canada have to take part in these rules if it isn’t necessarily better? Chances are good we will not even have an athlete in the Olympics. Maybe Sean McColl, but he only won the Olympic combined format back when no one cared about it. People care now. I believe only the top 20 men and 20 women go to the Olympics.

It just feels super uptight, like you can’t climb with your shirt off anymore. Where would competition climbing be in Canada if people never watched Josh Muller climb without a shirt? People would have stayed home instead of watching finals, and the sport may not have grown to the same degree.

Looking back on my memories, I have not seen Josh without a shirt! Impressive?

Oh god damn.

What were those early experiences of comp climbing like in Alberta? There seemed to be so many influential characters around to keep you psyched!

The competition scene in Alberta is amazing. Many of the climbers involved went on to start new gyms. Rock Jungle, Bolder, Grip-It were all started by AB/SK comp climbers, and now Blocs too. The majority of my closest friends I met through competitions too. It was definitely motivating to compete as a kid against people like Terry Paholek, who were always super supportive of everyone else competing.

It does appear that the Alberta / Saskatchewan comp scene was a thing of magic. Do you think those days are gone, or better put, what would it take to bring those days back? I guess it begs the question as to whether climbing has gone so mainstream that the fringe characters, which seemed to be everyone back in the day, have moved towards other fringe activities.

There are so many great people competing and hosting events. There are hundreds more kids than there used to be too. Actually most of the same key people are still there, but their roles have changed from a competitor to a coach or gym owner. The scene is still totally alive and well, my gripes are almost exclusively to do with the setting trends really. There are plenty of people that do like the volume only style though. We’ll just have to see if it is a fad or is here to stay. The rule changes I can live with, even though I would prefer longer time limits in the finals of both lead and bouldering.

What does your training schedule look like and how do you go about completing your goals?

My climbing schedule is probably not that different from most people’s. I spend 3-4 days a week at the gym, and my sessions are 2.5-3 hours. The difference is the quality of my days, and the structure of what I’m training. If I am supposed to be training X thing, I am training X thing. I warm up, do all my drills, and then go rest. Since I have been training so long on competitive teams, I know how to design a program structure and fill it with drills. I also don’t mind training the entire day, without sessioning any boulders at all. I might not even climb other than my warm up. For months at a time I will do things like warm up into campus board, hangboard, conditioning and then repeat.

To complete my goals, I obsess over them. I will map out every hold on climbs, watch every video, take screenshots of every move of the videos, and so on. I plan my life around trips to the climbs, and make a training program to peak for the trip. Then I just stick to it, and train really hard. I almost never go to the gym without a plan for the day.

Is there anything you do that is different than other people that our readers might learn from?

I don’t think I’m really much different, I think I just try harder than other people. Not only with how disciplined my training is, but how many muscle fibres I can recruit on a climb. Average people can summon about 60% of their maximum theoretical strength, while elite athletes can exceed 80%. Then on top of that, your body wants to keep some energy around for emergencies. With adrenaline and a high importance event, you can tap into it. Think of a mother flipping something very heavy off her child. On a climb I care enough about, I believe I can tap into that reserve consciously, like other high-level athletes. Several people have commented about how hard I can throw myself at something. I think most people could climb so much harder than they imagine if they actually tried as hard as their bodies are able to.

I can attest to that, seeing you climbing in the boulders! So where do you think you learned to try so hard or do you think it is something that can be learned?

I’m not sure honestly. I saw it in kids when I was coaching as well. It was really hard to get kids who didn’t care deeply to try super hard. But some did care and would dig super deep at pretty much everything we did. You can’t put your body through it if your head isn’t in it.

I guess when we talk about trying hard, we talk about a mentality but also some of the experiences you had growing up as a kid etc. When did you start climbing and when did it really take a hold of you?

My parents took me climbing for the first time when I was 6. I was always climbing trees and buildings. They had never climbed before that. I can’t really remember a time where climbing wasn’t the first priority in my life.

So what is on your mind for next year?

This summer the main objective is 5.15. Last year I climbed 5.14d, and did most of the moves in Disbelief which is “high end” 5.15b. I will have done two complete training cycles since last summer, and should be my strongest yet. I will try Ondra’s new route Sacrifice 5.15a to see if it suits me and actually feels easier than Disbelief. If not, I’ll just work Disbelief. I would also love to take a trip to Squamish, I haven’t been since I moved away from the west coast.

That would still be the first Canadian 5.15! Is that something that motivates you or are you goals more personal?

It has been a goal of mine to climb 5.15 ever since I watched Chris Sharma climb things like Jumbo Love for the first time. When Evan first graded Honour and Glory 5.15 it didn’t take anything away from the goal, I don’t care about being the first too much, even though that would be really cool. In fact I was really excited there was a 5.15a in Canada and went straight for it. Unfortunately it wasn’t quite that hard, but there are several other options now that Ondra visited Canmore.

Do you have any ambitions for an overseas trip or is that further down the road?

It would definitely be further down the road. Not only can I not really afford it, all my goals happen to be in Canada or at bouldering area in the States.

Well thanks again for chatting with us Miles! All the best for 2019 and can’t wait to see what you come up with!